[Research Report] AMR Policy Update #2: WHO’s First Report on Fungal Infection—Bridging the Gap Between Clinical Practice and R&D

- Home >

- Information >

- News >

- [Research Report] AMR Policy Update #2: WHO’s First Report on Fungal Infection—Bridging the Gap Between Clinical Practice and R&D

<POINTS>

<POINTS>

- The two reports released by WHO in April 2025 highlight a severe shortage of antifungal agents and diagnostic tools for IFDs, warning that this represents a serious global public health challenge.

- Fungal infections are life-threatening, particularly for immunocompromised patients, and the emergence of drug-resistant fungi is further exacerbating the problem.

- Although new antifungal agents are under development, their number remains limited. Existing agents also pose significant challenges such as adverse effects and drug–drug interactions (DDI), underscoring the urgent need for innovative treatments.

- On the diagnostic front, especially in low- and middle-income countries (LMICs), advanced laboratory capacity is lacking, making it difficult for patients to receive timely and appropriate diagnosis and treatment.

- WHO recommends promoting research and development, strengthening economic incentives, supporting education and awareness among healthcare workers, and establishing robust global surveillance systems.

On April 1, 2025, the World Health Organization (WHO) released its first-ever comprehensive report on invasive fungal diseases (IFDs) in its long history. The two reports published, “Antifungal agents in clinical and preclinical development: overview and analysis” and “Landscape analysis of commercially available and pipeline in vitro diagnostics for fungal priority pathogens,” reveal the critical state of antifungal agents and diagnostics.

What Are Fungal Infections? From Familiar Presence to Pathogen

Fungi include molds, yeasts, and mushrooms, and are among the earliest microorganisms recognized, utilized, and coexisted with by humankind. They not only play an essential role in maintaining the global environment by decomposing organic matter such as the remains of plants and animals, but have also contributed to the production of fermented foods and beverages such as alcohol, miso, and cheese, as well as to the development of medicines like penicillin. Even today, fungi continue to support our daily lives behind the scenes.

On the other hand, some fungi can cause a group of diseases known as mycoses, which harm the human body when immunity is compromised. These fungi are referred to as pathogenic fungi. Mycoses caused by pathogenic fungi are broadly classified into two categories based on the site of infection. One is superficial mycoses, which manifest as skin conditions such as athlete’s foot. The other is IFDs, which affect internal organs, including candidiasis and mucormycosis, as highlighted in the WHO reports. IFDs can have severe consequences for immunocompromised individuals, such as patients undergoing cancer chemotherapy, people living with HIV/AIDS, and organ transplant recipients, are associated with a high risk of life-threatening outcomes.

In principle, IFDs are primarily treated with antifungal agents; however, many cases remain difficult to manage, and there is no antifungal agent effective against all types of fungi. Moreover, in recent years, fungi that have acquired drug resistance, referred to as antimicrobial resistance (AMR), have emerged, posing a global challenge. Even in common fungal infections, such as oral or vaginal candidiasis, drug-resistant fungi have been reported. This not only limits treatment options and increases the risk of recurrence but also raises significant public health concerns.

Aging population and advancement in medical technology has led to an increase in patients with weakened immune systems, the incidence of IFDs is also rising in Japan. A major challenge in managing these infections lies in their diagnosis and treatment. Because fungi share structural similarities with human cells, it is difficult to discover specific diagnostic markers that can uniquely identify fungi, as well as to develop antifungal drugs and diagnostic tools that target fungi without harming humans. Therefore, the development of antifungal therapies and the establishment of clinical practice guidelines are considered urgent priorities. This issue was also addressed in HGPI Special Seminar in 2024.

WHO’s Response to Treatment and Diagnostic Gaps

The reports published by the WHO also highlight the significant lack of effective treatments and accurate diagnostic tools for IFDs. The WHO points out that there is a substantial gap between the needs in clinical practice and the available medical resources, emphasizing that rapid efforts in innovative research and development (R&D) are essential to address this challenge.

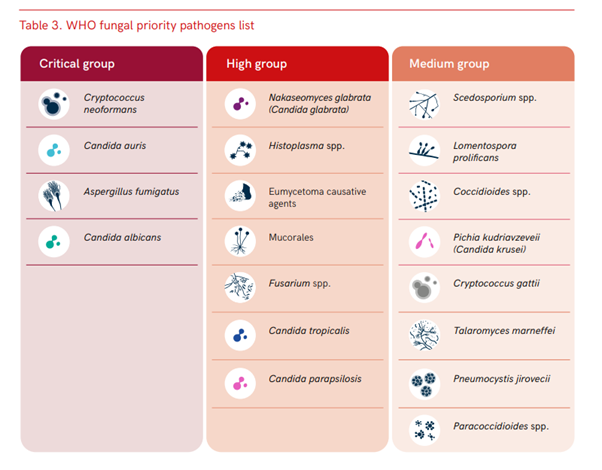

In 2022, the WHO published the Fungal Priority Pathogens List (FPPL) for the first time, clearly identifying the fungal pathogens that should be prioritized in research and development. The fungi in the top ‘critical priority’ category are extremely dangerous, with mortality rates reaching up to 88%.

However, addressing these challenges is not straightforward due to the lack of diagnostics, difficulties in the supply of antifungal drugs, and the time and cost required to develop new treatments. In response to this situation, the WHO recommends a multifaceted approach, investing on global surveillance, expanding financial incentives for drug discovery and development, funding basic research to help identify new and unexploited targets on fungi for medicines, and investigating treatments that work by enhancing patients’ immune responses.

In addition, knowledge about fungal infections and resistant fungi is still not sufficiently widespread in clinical practice, and there are many cases where the tests necessary for appropriate treatment are not performed. Strengthening educational support and awareness-raising activities will therefore be important moving forward. The WHO has also conducted review on the global antifungal preclinical and clinical pipeline (this review is also cited in the reports), aiming to reinforce measures against IFDs and antifungal resistance, and is also developing an implementation blueprint for the FPPL. With the revision of the Global Action Plan on Antimicrobial Resistance (AMR) scheduled for 2026, which is the first update in ten years, further progress is anticipated.

The key points of each report are as follows.

Report 1 “Antifungal agents in clinical and preclinical development: overview and analysis”

This report clarifies the current state of research and development (R&D) of antifungal agents and aims to promote the development of new treatments that address the most urgent unmet medical needs. It also focuses on challenges related to access to access and availability particularly in low-resource settings.

Present antifungal drug arsenal

- Most approved antifungal drugs commercially available pose challenges, including frequent adverse events, significant drug–drug interactions, limited dosage forms, and the need for prolonged treatment courses (often ‘in-hospital’).

- Within the range of antifungal medications available to adults, there is a lack of antifungals with a child-friendly formulations for pediatric use.

Newly approved antifungals

- In the past 10 years, only four new antifungal drugs have been approved by the United States Food and Drug Administration, the European Medicines Agency, or by the Chinese National Medical Products Administration.

- All four approved drugs have both in vitro and in vivo data for activity against at least one critical priority pathogen (CPP) according to the WHO Fungal priority pathogens list (FPPL); two candidates have activity against three CPPs, one agent shows activity against two CPPs, and one agent against one CPP.

- Only one of the approved drugs meets any of the criterion agreed by WHO to assess innovation.

- Three out of the four approved drugs have a reduced risk of DDIs.

Pipeline of antifungal drugs in clinical development

- Nine agents are currently in clinical development against priority fungal pathogens according to the WHO FPPL.

- Seven agents out of nine currently have in vitro and in vivo evidence of activity against at least one CPP according to the WHO FPPL.

- Two candidates have activity against all four CPPs, one candidate has activity against three CPPs, and one agent shows activity against two CPPs.

- Among the nine antifungal drugs in clinical development, four meet at least one innovation criterion. Of these, two meet all four innovation criteria, while two meet one innovation criterion.

- Overall, antifungal agents in the clinical pipeline combined with those approved in the past decade are still insufficient, when considering the key targets and the innovation needed, to address the therapeutically challenging fungal pathogens identified by WHO.

Report 2 “Landscape analysis of commercially available and pipeline in vitro diagnostics for fungal priority pathogens”

This report systematically describes in general terms public health laboratory systems and the roles of related facilities (from clinics and other healthcare institutions to reference-level laboratories), with a focus on low- and middle-income countries (LMICs), in order to clarify the challenges in diagnostic systems for IFDs. The report also summarizes specific diagnostic approaches (e.g., phenotypic methods, non-culture-based methods, antifungal susceptibility testing (AFST), and resistance testing) and examines accessibility and ease of use for each method.

Gaps and Needs in In-Vitro Diagnostics for Fungal Priority Pathogens

- Although diagnostic methods exist for priority pathogens, most tests require specialized equipment and highly trained personnel, making them difficult to implement at level I and level II facilities. In LMICs, testing is largely restricted to regional or reference-level laboratories.

- There is a pressing need for simple diagnostic tools that are rapid, accurate, affordable, and capable of detecting a wide range of fungal pathogens, while being suitable for use at or near the point of care.

- For fungal pathogens not included in the Fungal Priority Pathogen List (FPPL), non-culture-based diagnostic methods are extremely limited, and testing is generally confined to reference-level laboratories equipped with advanced facilities.

Appendix I: Fungal Priority Pathogen List

Reference: WHO fungal priority pathogens list (World Health Organization, 2022)

Appendix II: WHO Criteria for Assessing Innovation

New Class: Belongs to a new chemical class structurally distinct from existing antibiotics.

New Target: Acts on a biological target that has not been targeted by existing antibiotics.

New Mode of Action: Inhibits or kills pathogens through a mechanism different from that of existing antibiotics.

Absence of Cross-Resistance to Existing Antibiotics: Effective against resistant strains that have already developed resistance to currently used antimicrobial agents.

References

- World Health Organization. (2022). WHO fungal priority pathogens list to guide research, development and public health action. Geneva: World Health Organization. Licence: CC BY-NC-SA 3.0 IGO.

- World Health Organization. (2025). Antifungal agents in clinical and preclinical development: Overview and analysis. Geneva: World Health Organization. Licence: CC BY-NC-SA 3.0 IGO.

- World Health Organization. (2025). Landscape analysis of commercially available and pipeline in vitro diagnostics for fungal priority pathogens. Geneva: World Health Organization. Licence: CC BY-NC-SA 3.0 IGO.

- World Health Organization. (2025). WHO issues its first-ever reports on tests and treatments for fungal infections [Press release]. WHO. https://www.who.int/news/item/01-04-2025-who-issues-its-first-ever-reports-on-tests-and-treatments-for-fungal-infections.

- World Health Organization. (2025). Antifungal agents in development – First WHO global pipeline review of clinical and preclinical antifungal therapeutic products [Web page]. Global Observatory on Health R&D. Retrieved June 26, 2025, from https://www.who.int/observatories/global-observatory-on-health-research-and-development/monitoring/antifungal-agents-in-development.

Acknowledgements

Kazutoshi Shibuya (President, The Japanese Society for Medical Mycology / Professor, Department of Surgical Pathology, Toho University)

We would like to express our sincere gratitude for Dr. Shibuya’s valuable advice and comments in the preparation of this report.

Authors

Eri Cahill (Associate, Health and Global Policy Institute)

Yui Kohno (Manager, Health and Global Policy Institute)